*Some names were changed to conserve anonymity

Focusing on photos of loved ones, Mandy Keets strains to remember who they are. The drugs shattered her memory, and as she recovers from her fourth overdose, the faces of her loved ones are a mystery to her.

This incident occurred six years ago. Keets is now five years clean, and now her family’s faces serve as reminders as to why she got clean in the first place.

“The first time I ever used drugs, I was 13 years old,” Keets said. “I was with my older cousin, [who] I looked at like she was my big sister, and she was using when we were at a party.”

Disclaimer: Keets’s story is written to raise awareness of the dangers of drugs and is in no way meant to glorify drug usage. Her story highlights that the teenage years are traditionally a time of personal exploration—due to an increased likelihood of impulsive decision-making—irresponsible drug usage happens.

“Studies show that the younger a person engages in substance use, the higher their chances are of being diagnosed with a substance use disorder in the future,” head clinician at Ken Starr’s Medical Detox, Recovery, and Wellness Care Summer Littlefield said. “Those percentages rise as the age of [the] first [drug use] gets younger.”

Even though drugs were not prominent for Keets at a young age, her mom left, forcing her into adult responsibilities and denying her a positive maternal force.

“Overall, I had a really good life,” Keets said. “I just always felt like I was missing something [due to my mom’s absence]. I never felt like I was good enough.”

Despite losing her relationship with her mom, Keets was still able to excel socially and academically.

“In high school, I played sports, was on the homecoming court, got really good grades, [and] was in 4-H and FFA,” Keets said. “I was really popular. I was a good kid. I didn’t get in any trouble [and] looked down on people who did drugs.”

Keets didn’t rely on drugs in high school, but peer pressure led her to experiment at parties.

“I didn’t do [drugs] for a really long time after [the first time],” Keets said. “The next time that I used, I was at a party in high school. I was probably 16. And then again, [I used] just because everybody was doing [drugs].”

According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse’s annual survey, 1 in 3 high school seniors reported experimenting with illicit drugs in 2022 (American Psychological Association).

“When I did that first line, I felt like I had no pain,” Keets said. “I didn’t feel empty anymore. I didn’t feel sad that my mom left. I didn’t feel anything.”

Using drugs might alleviate pain because they affect the reward center of the brain. Pain reduction can increase some users’ belief that they need drugs to survive.

“Our brain on the best day and [in] a healthy environment would go up to 100 nanograms of dopamine,” Littlefield said. “[Using] drugs and alcohol [makes dopamine levels] go way past that threshold. The more you inundate your brain with those abnormally high amounts of dopamine, your brain starts changing its level of homeostasis to meet that new level. So, it becomes more and more dependent on that higher level—that false level of dopamine—which then can lead to addiction and thinking that that drug is more important than air, water, and food because your brain now thinks that it needs that high level to survive.”

Since drugs release dopamine into the brain, Keets felt as though they were relieving her pain. With that belief, when Keets exited high school and found herself in a relationship with an abusive boyfriend, she heavily relied on drugs.

“I was with the star quarterback, and everything looked perfect, [but] he was really abusive,” Keets said. “We started doing drugs, and I didn’t feel any pain. I got to numb that whole situation out. [Then,] I started doing drugs a lot because it was to escape the reality. And then I got addicted because I was doing it so much. I needed it every day to function.”

Keet’s drugs of choice were uppers, such as methamphetamine and cocaine.

“I [liked] uppers,” Keets said. “I [liked that the drugs] helped me stay up [because] I had kids and I had a job, and so I felt like it just helped me stay up and helped me do things.”

During her addiction, Keets also drank daily to further her detachment from reality.

“I also drank a lot in my addiction,” Keets said. “I would put Baileys in my coffee. Then, I would go [drink] beer in the afternoon, and then hard alcohol in the evenings. It was pretty bad for a while.”

Keets continued these habits for two and a half years, and nobody noticed her struggles with substance abuse—including herself.

“I thought that I was functioning,” Keets said. “I had a job, I had a car, I still had my kids. I [also] struggled with an eating disorder from the time I was really young, and it helped me stay thin, so I didn’t have to throw up as much [while using]. So, people on the outside didn’t know that I was using [drugs] because they just thought that my eating disorder was really bad.”

However, the ramifications of her drug usage increased dramatically when she changed her methods of getting drugs into her body.

“I went from snorting [methamphetamine] to smoking it to [intravenous usage],” Keets said. “So when I started slamming it, that’s when I noticed that I started going downhill. I lost my job. My relationship failed. I lost my kids. I lost everything.”

When Keets lost her kids, the court presented her with an ultimatum.

“[The court said] I either went to rehab, or I wasn’t gonna get them back,” Keets said. “So, I checked myself into a rehab, and I detoxed in rehab.”

The rehab facility that Keets checked herself into wasn’t medically assisted, but it was somewhere where she could be monitored and held accountable for getting clean.

“[People at the rehab facility] watch you really closely and make sure that you’re okay and that you’re not getting too sick,” Keets said. “It was like a three or four-day detox, and you’re isolated in detox, so it’s just you in this room. They give you juices and electrolytes, and they bring you your food. But, you’re sick and you’re tired and you’re miserable. It’s terrible.”

Detoxing is the first step to getting clean, but it puts the body through withdrawal, which comes with side effects ranging from flu-like symptoms to seizures.

“[Detoxing off] opiates could feel like the worst flu of your life,” Littlefield said. “Alcoholic [detox can give a person] increased anxiety [or] a seizure at worst. Sweating, shaking, stomach issues, [and] insomnia are like the basic [detox side effects].”

Ken Starr’s medical detox facility specializes in outpatient rehab. Clients are given medication to help with detoxing but get to go through the process at home.

“[Ken Starr offers] a medication-assisted treatment, [which] provides medication to help support and stabilize someone while they’re withdrawing,” Littlefield said. “Also, [we] support long-term recovery with various medications that help with cravings, blocking opiate receptors. If you take [the medication], you get violently ill when you drink, so it’s a great motivator to not drink.”

Ken Starr’s medical detox facility offers personalized help, but recovering addicts can also attend group therapy meetings.

“So, we have like a 12-week curriculum [for group therapy],” Littlefield said. “A lot of it is mental health based, and the majority of our group [sessions] is really getting to the underlying causes of why someone struggles with addiction.”

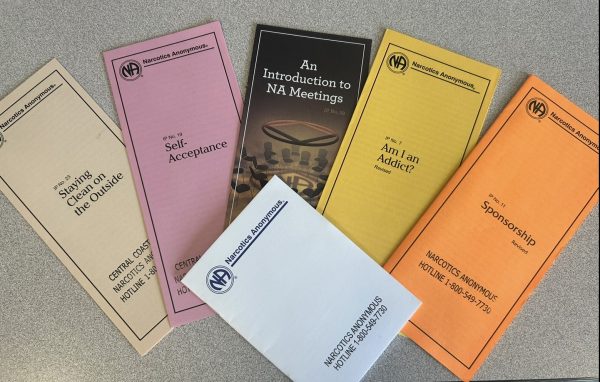

Although Keets didn’t attend Ken Starr’s medical detox facility, she found success with group therapy at Narcotics Anonymous (NA).

“Once you’re over [detoxing,] you get to start incorporating [programming] into your daily life,” Keets said. “So, then I started to go to meetings with the girls [in the detox facility] and got a sponsor.”

NA offers a safe space for all recovery addicts and allows them to find people with similar experiences.

“As [new members] listen, they see that [the people in NA are] their peers. These are people that have done the same thing that they did. They speak the same language,” NA representative Clinton Murphy said. “So, that’s an attraction [to come back to meetings] because they know that they’re seeing people that can relate to them.”

Murphy achieved sobriety in 1987 and is an active member in the recovering addict community. Growing up with both his parents suffering from addiction, Murphy is an example of becoming an addict due to nurture.

“In 1986, I moved here from Los Angeles. I went to Cal State LA. I was a social work major,” Murphy said. “I thought that if I was educated enough, I would be functional, but it didn’t work.”

Murphy also served in the military and associates some of his drug use to self-medicating for his PTSD. However, he still didn’t believe he was an addict at the time.

“I was in a lot of denial that I really needed help,” Murphy said.

Every person struggling with addiction has a different story and upbringing. Someone’s substance abuse doesn’t depend on one life factor.

“[The underlying cause of why someone is an addict can be] that inner-critic, lack of boundaries, trauma, [and] attachment, all the foundational pieces that maybe have led us to struggle in these ways,” Littlefield said. “[During group therapy], we do talk about self-compassion and shame, and [have] clients gain an understanding of these ingredients that led to them struggling.”

Going to group therapy can help an addict feel less alone and can help them live their day-to-day lives without needing drugs.

“We really want to reduce shame and increase self-compassion,” Littlefield said. “We teach a lot of coping skills, stress management, effective communication, distressed tolerance, [and] emotional regulation.”

Overcoming addiction is a big feat, but it leads to a better life overall.

“[I would describe my life now as] wonderful. I have five years clean,” Keets said. “It’s not easy. There are really hard days, and then there are really good days. I’ve walked through a lot of stuff that has been hard, and I’ve wanted to get loaded, but I have a good support group that won’t let me get loaded, even when I want to. I surround myself with people that have a good attitude. It’s awesome.”

Keets is now heavily involved in the recovery community. She is the secretary of NA and offers her help to other women in NA as a sponsor.

“[A sponsor helps] you walk through the steps, [and] any problems that you’re having,” Keets said. “[They support you in] the good times [and] the bad times. It’s like a mentor, basically. Somebody [who] you can call all the time and just talk to.”

Ending addiction is a day-by-day process. Just because someone is five years clean doesn’t mean they don’t struggle with the thought of using drugs again.

“The thought of using drugs is always in our head,” Murphy said. “It never goes away.”

Addiction doesn’t make someone a bad person. Most people who struggle from addiction are trying to cope with their struggles. However, seeking help for substance abuse is a crucial way to better one’s life.

If you or a loved one struggles with substance abuse, there are many resources to help with recovery and remind you that you aren’t alone.

Resources on AGHS’s campus can be found in the front office through Advocacy Services Coordinator Lisa Martinez.

“We have therapy on site,” Martinez said. “Right now, [AGHS] has four clinicians who come on site to help out [students] with a variety of things. Two of those clinicians actually are clinical psychologists, so that really helps out.”

If finding help on campus seems daunting, here are more resources below:

Aspire (Counseling, Therapy, and Medication Assisted Treatment)

Camino a Casa by Casa Pacifica (Intensive Outpatient Program for teens for mental health)

The Haven at Pismo (intensive inpatient addiction treatment center): (805) 202-3440

Turning Leaves Recovery Life and Wellness Coaching (life-coaching and therapy)