AGHS principal goes the extra 100 miles for Nisei students during World War II

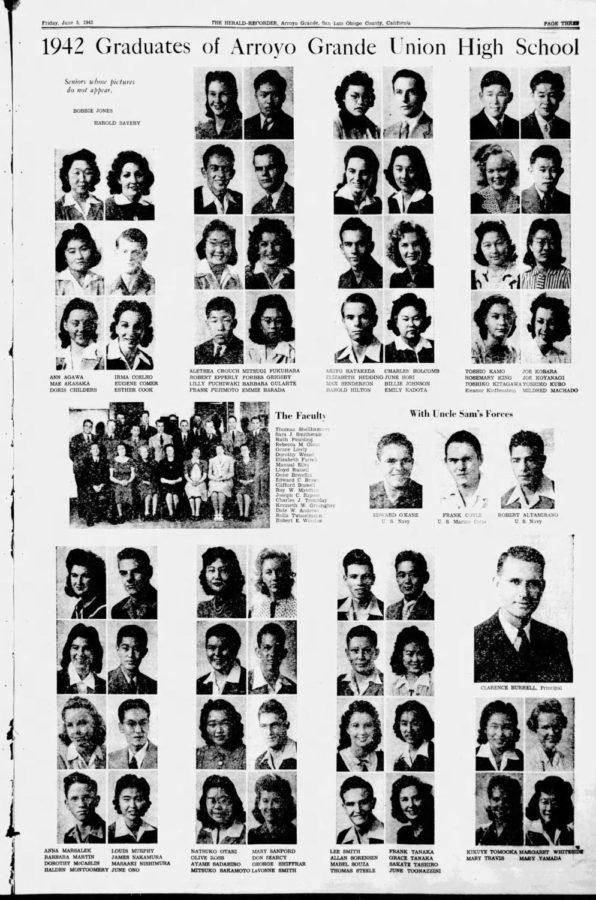

The graduating Arroyo Grande Union High School class of 1942.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is one of the most tragic actions in our nation’s history. Those lucky enough to return home often lost their houses, jobs, and businesses. Few stood up for these innocent Americans that were treated as criminals, but in Arroyo Grande locals stood up for their neighbors and friends to keep the Nisei from losing everything.

This history could have easily faded away, but Jim Gregory, a retired AGHS teacher, has an interest in the past of the small community. He has written multiple books on Arroyo Grande’s history and has prevented many facts from being forgotten.

“I try to work local history [into lessons] to help students understand that we are a part of history too,” Gregory said.

If not for Gregory and others who have decided to research the past, the heroic actions of many locals could have been overlooked, but instead, we now know what Clarence Burrell did for Japanese-American students who attended AGHS.

Burrell worked at Arroyo Grande Union High School (AGUHS) from 1929 to 1948. Through both the Great Depression and World War II, Burrell pushed to hold the school together.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, rumors of internment for Japanese-Americans circled. Of the 58 seniors at the school, 25 were of Japanese descent. In response, Burrell told the teachers to speed up classes for those 25 students in an attempt to get them to graduate before they were taken away. They fell short of accomplishing this goal, and on April 30th, 1942 busses came to AGUHS.

The school year came to an end, and Burrell was not able to graduate many of his students. Burrell drove over 100 miles to Tulare and gave the seniors their diplomas outside their makeshift homes in livestock stalls.

Burrell’s actions were not backed by popularity at the time. Support for Nisei was scarce, but Burrell fought for his students anyway.

“[He had a] great deal of compassion, that’s why people remember him so much,” Gregory said.

Many other people of Arroyo Grande stepped up to help combat the injustice of the internment, even if it hurt their relationships and businesses.

The Ikedas are a local family of farmers that have been in the area since the 1920s. When their family was taken away, the oldest of them, Kazuo (“Kaz”) Ikeda was too elderly to be taken, or to take care of himself; the Loomis family of Arroyo Grande took care of him while his family was gone, and held the personal items of the Ikedas’ in a storage building.

“[The Nisei] were people they grew up with, they were their friends,” Gregory said.

A lot of the locals indeed saw the Japanese Americans as equals, and the federal action unjust, but for many, that wasn’t the case.

The Loomis family owned a store at the base of Crown Hill, people would come in and tell the them that they must get rid of the Ikeda living with them. Along with this, the storage facility where they were holding the Ikedas’ items was broken into and vandalized.

The unpopularity of supporting the Japanese-Americans shows the nobility in the actions of those who supported them, like Burrell and other locals. Arroyo Grande was, and still is a big farming community, and the farms left unattended could have been ruined, however, many neighbors took over and helped maintain the farms for the Nisei who were gone.

These actions by Burrell and others from Arroyo Grande helped maintain the livelihood of those who were forcefully removed from their houses and jobs. Burrell continued to influence the community through education until the end of his career in AG. Burrell employed and inspired many teachers who would go on to have profound impacts on local education.

“[Burrell was] an inspirational leader to keep the school together,” Gregory said.

Burrell hired Ruth Paulding, whose name now represents the middle school in the shell of AGUHS, as well as Max Belko, who is remembered as a college football player and a US Army Lieutenant, as well as a fantastic basketball and football coach in AG.

In Burrell’s final years in Arroyo Grande as principal, he helped negotiate for the land where the current high school resides.

After finishing up at AG, Burrell moved on to be the Superintendent in San Leandro where he would continue to influence faculty and help students succeed.

For everything that Burrell has accomplished and for all the people he has inspired, more people should know of him and his dedication to Arroyo Grande and education.

“[Burrell] kept the community proud,” Gregory said.

Cory Wack is a senior, assistant to the editor in chief, who has an undying love for objective journalism. Besides his consuming devotion to the news,...