Peyton Morris (‘26) was using the 500s wing bathroom when the vape sensor began beeping.

“I just went outside. I knew that I didn’t do anything or mess with anything,” Morris said.

Since returning back to school, many students experienced a similar situation with the installation of the new vape sensors. This new policy is meant to increase safety in bathrooms.

“The idea behind the vape sensors was really to take back the bathrooms, and make sure that the bathrooms are a place where kids can feel comfortable going to the bathroom,” Campus Resource Officer Bradley Hogan, said.

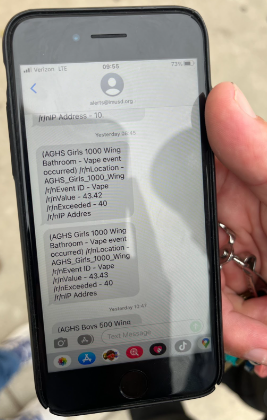

When a sensor goes off on campus a notification is sent to staff. The vape sensors can tell the difference between THC, vape, perfume, and if it is being tampered with. The identification of these different products can help curb the use of addictive products in the school bathrooms.

However, what happens during these sweeps is not common knowledge to many students, and recently, the policy has changed. Now, administrators don’t search students on the first occasion. On the second occasion, students now fill out a form, and then the third time, they are searched.

Students caught vaping could be sent to Lisa Martinez, the Advocacy Services Coordinator for the Student Wellness Center, who evaluates what the student needs to do to change their behavior.

“The first thing I tell [the students] is ‘thanks for coming in, that it took a lot of strength to realize you need support.’ Some kids want support and get better, some kids honestly don’t. And they actually become hardcore drug addicts and eventually at some point they get expelled from our school,” Martinez explained.

After the initial meeting, students are put on a behavior contact with requirements such as community service and reflections.

“It might be a good number of counseling sessions; we have therapists here on site who could provide those resources or services, or somebody can go off campus to get their own therapy if they wanted to,” Martinez said.

When a struggling student comes forward for help, there is a confidentiality policy, and nothing shared with Martinez can be spoken about outside of the room unless the student is a danger to themselves or others.

“This is a safe place. This is somebody who has strength and the courage to come forward and say ‘I am struggling with this,’” Martinez said.

“I [do, however] have to report if the child is self-harming, [or if] they want to harm somebody or somebody’s harming them.”

After connecting with a student, Martinez refers them to on or off-campus therapy. Another one of these programs is Second Step. Students voluntarily get personalized help, listen to speakers who previously struggled with addiction, and have opportunities to earn community service.

“Ultimately, the program is here to help kids lessen their usage and then to hopefully at some point, become sober,” Martinez said. “It’s like two steps forward, one step back, two steps forward, one step back. We call it a no-harm model. We want to help them where they are”