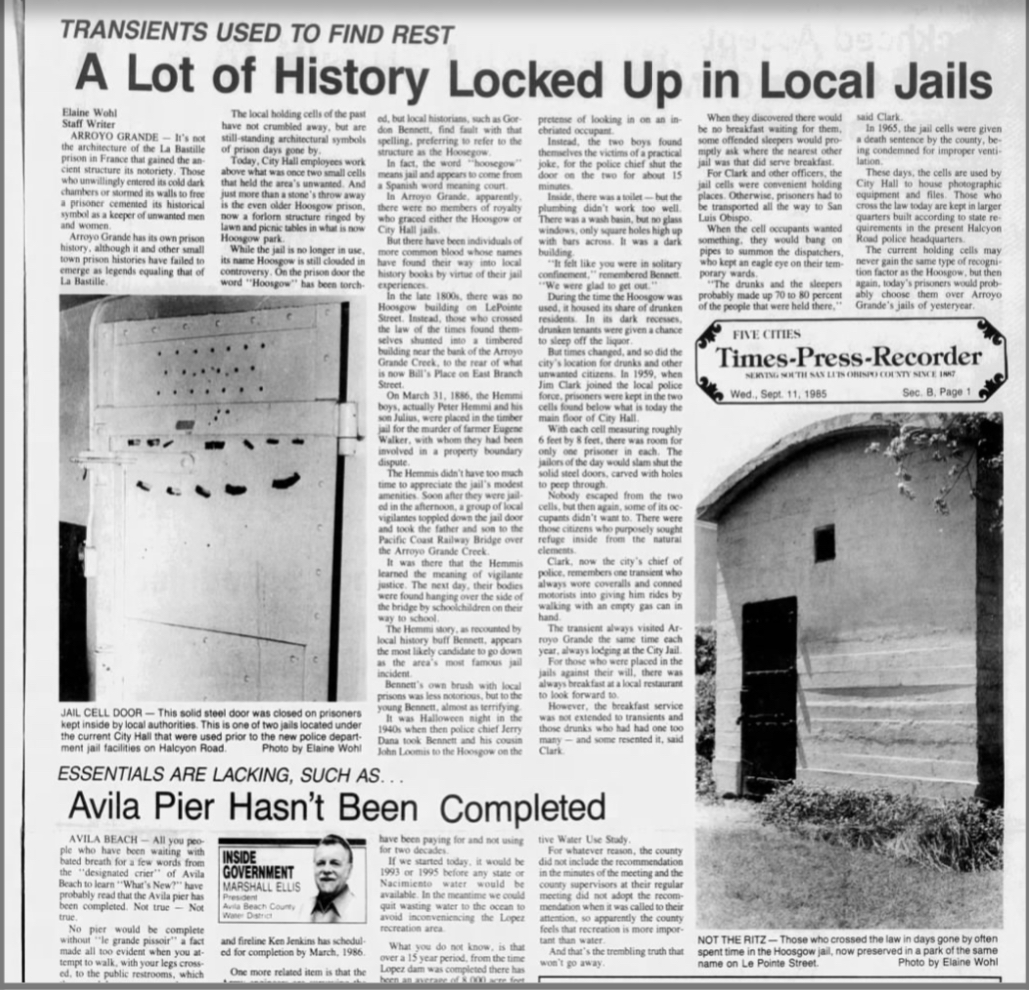

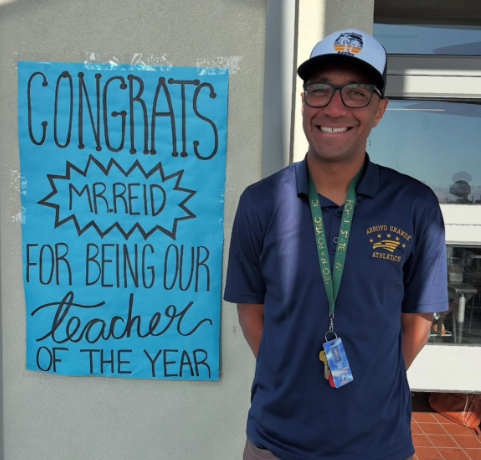

In the 1930s, a blacksmith by the name Jack Schnyder walked up to a cement, one-room jail. He took out a blow torch and torched the word “Hoosegow”—the name residents referred to the jail as—into the iron door. By doing so, the jail became a historical landmark, and would hold the remembrance of the outlaws of Arroyo Grande, California.

Built in 1906, the Hoosegow is located on Le Point Street, above the parking lot behind Andreini’s. While it now stands unopened and untouched, a hundred years ago, it was a cell for drunks and clam poachers.

“If [the inmate was] a drunk, he would spend the night here,” Jim Gregory, President of the Arroyo Grande Historical Society and retired AP European History teacher, said.

The drunk would then be brought in front of an amicable judge, an example being Judge Rocky Dana, but he didn’t just deal with drunks.

“A lot of his cases seemed to involve under-sized clams,” Gregory said. “A lot of people poached clams, and they would always come up before Judge Dana [because], for some reason, he [was] the clam judge.”

The Hoosegow also kept higher level criminals, but they would only be held there for small amounts of time, until the Sheriff or the Deputy arrived to pick them up.

“[The county jail] was in the basement of an old, beautiful, county courthouse that was built in 1874,” Gregory said.

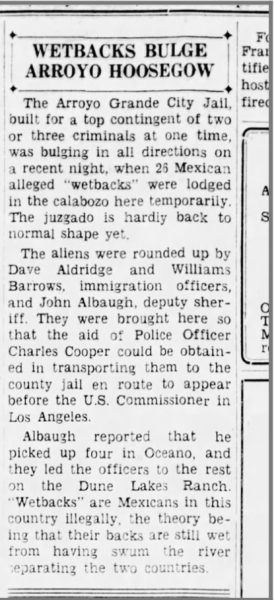

The county jail was able to hold more people than the Hoosegow—which for the most part, would hold a maximum of one to two people at a time. However, there was an exception.

In an article published in the Arroyo Grande Valley Herald, a situation is described where 26 Mexicans were held in the Hoosegow at once because they were accused of coming into the country illegally.

Outlaws were common in SLO county in the late 1800s, and one of Gregory’s favorites is a stagecoach thief named Dick Fellows.

“He robbed a Santa Barbara stage twice, a San Luis Obispo stage, and a stage from King City once, before he was finally caught by a Wells Fargo detective,” Gregory said.

What made Dick Fellows so charming was his bad luck with horses. In almost every attempted getaway, Dick Fellows’s plan was ruined by a horse—in his last attempt he assaulted a deputy while staying in the Santa Barbara County Jail, but got caught shortly after because of a horse.

“Fellows, instead of eating his breakfast, jumped the deputy [and] knocked him to the ground,” Gregory said. “[He] dashed out the front door of the jail, jumped onto a horse, [and] went pell-mell for leather down Santa Barbara street. [He] made a sharp left turn and his horse ran into another horse.”

Criminals, like Dick Fellows, roamed the streets of San Luis Obispo County. However, not all of them escaped quite as often as he did.

“[Peter Hemmi, age 52, and P. J. Hemmi, age 15] were a father and son who were lynched from the Pacific Coast Railway Bridge at the foot of Crown Hill in 1886,” Gregory said.

The Hemmis went to the Calaboose—the jail used before the Hoosegow—on account of murder in the first degree after an ongoing land dispute led P. J. to shoot a neighbor and his wife.

Every time someone passes the Hoosegow and wonders to themselves what it is and who stayed there, they will be inadvertently remembering the old outlaws, and Schnyder, who put the Hoosegow on the map.

For more information regarding the outlaws of Arroyo Grande, click on this video of Gregory telling more stories.