The Restricted Section: Speak

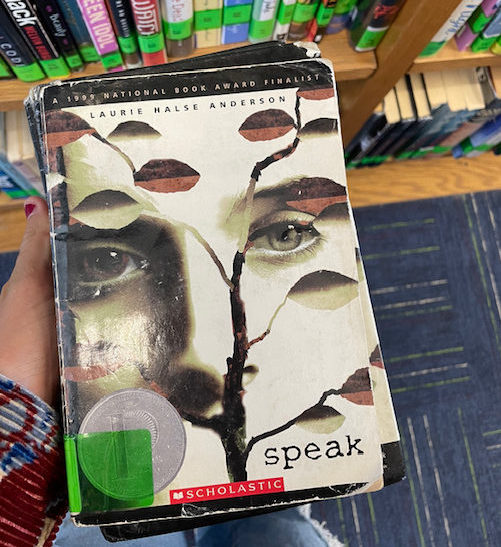

The front cover of AGHS library’s copy of Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak

Speak, a 1999 young adult novel written by Laurie Halse Anderson was named one of the “Top Ten Most Challenged Books of 2020” by NPR. This book is a hat trick being “banned, challenged, and restricted.”

The novel tells the story of Melinda Sordino. She has lost her friends, her social status, her GPA, and her voice. Melinda has gone essentially silent to the outside world, the story told via her internal monologue and occasional spoken word.

The story follows Melinda all throughout her freshman year, starting with the first day of school and coming to a close with the last. At the beginning of the book, readers are blind to Melinda’s silence and the reason behind it. As the story unfolds, there are hints and clues left in the text and Melinda’s memory as to what happened that left her so afraid to use her voice, unable to engage with the supposedly life-changing prospect of beginning high school.

Despite being highly esteemed with over twenty awards to its name, educators and parents alike found reasons to request for Speak to be pulled from shelves and out of students’ lives. Two public times that the book was challenged were in 2010 and 2013.

In 2010, in Republic, Missouri, an associate professor at Missouri State University “cautioned parents of the Republic School District that Speak’s rape scenes were akin to “soft pornography” and should not be used in the school’s curriculum.”

In 2013, in Sarasota, Florida, a group of parents at a local middle school “became outraged when they equated the book Speak about a 13-year-old girl being raped as “pornographic.”

The novel is hardly the “soft pornography” that some claim. The only relatively sexual content is restricted to just a few lines of a girl finally revealing and painfully reliving her trauma.

To claim that the book is wholly about rape deflects from the core of the story and the character’s development for a novel so clearly about mental health. From the beginning, it is clear that Melinda struggles with anxiety, depression, and PTSD. It’s not something that has to be hidden by metaphors and flowery language. The main character’s grapple with the psychological damage inflicted by her rape is clear.

For the majority of the book, Melinda embodies the more physical symptoms and signs of depression. Her grades slip beyond repair, except for the class with the one teacher who can truly see her. She’s apathetic about her school and social life. She cuts class to spend time by herself, hiding from the world. She sleeps more than anything else and spends her waking hours in bed or on the couch unless forced to be somewhere else.

The author brilliantly explores mental health and trauma in a way that isn’t cliche or overdone, where the character spends all their time crying or acting in the way other pieces of media have told society to expect mentally ill teenagers to act.

*Trigger warning for self-harm and suicidal thoughts next few paragraphs*

“I open up a paper clip and scratch it across the inside of my left wrist. Pitiful. If a suicide attempt is a cry for help, then what is this? A whimper, a peep? I draw little window cracks of blood, etching line after line until it stops hurting.”

Anderson’s depiction of suicidal thoughts and self-harm are incredibly realistic and relatable to those who have struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts as well as intertwined with the character. This is the only explicit mention and description of self-harm throughout the book, providing insight into Melinda’s many attempted coping mechanisms. The response from Melinda’s parents is deeply troubling as well.

“Mom sees the wrist at breakfast.

Mom: ‘I don’t have time for this, Melinda.’

Me: ”

Both the parental commentary and unique formatting of conversation throughout the novel, particularly in this scene, make for a more introspective read and much easier for readers to connect with the main character, even if readers haven’t experienced anything close to what Melinda goes through.

Invalidation of mental health, particularly from parents, is a timeless concept. This idea was relevant when the book was written in the nineties. The problem persists with modern teenagers and the overall exacerbated battle with depression on the back end of the pandemic.

The format of the dialogue in this book also lends a unique storytelling and reading experience, emphasizing the fact that Melinda struggles to use and find her voice. Nearly every instance of dialogue is told in almost a script-like format, a way to showcase Melinda’s silence and the surrounding dissatisfaction. Her high school world is forcing normalcy upon her, something that she fears and rejects.

This specific writing technique is also used to demonstrate Melinda’s character growth as the book goes on. By the end, there are no longer blank spaces where Melinda is supposed to be speaking. Instead, willing sentences fill the frames.

It’s heartening to be able to grow with Melinda and get a taste of what it’s like to develop the kind of solidarity that young women should have with each other. The literary techniques in the creation of this book work hand-in-hand with a solemn message. This crafts an incredibly important story for students who wish to read along those lines and delve into heavier topics.

One of my only critiques of the book concerns the plot.

There isn’t much of a plot or a storyline to follow. This is what some call a character-centric storyline, where the main focus of the book isn’t the standard story arc, with an opening, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Character-centric storylines tend to follow a specific character’s journey and monologue. While most plot-centric storylines have more of a focus on the destination, character-centric storylines are about what happens in-between and with the character rather than the story as a whole.

There is nothing wrong with character-centric storytelling, specifically in coming-of-age YA novels such as Speak. A majority of popular coming-of-age stories are character-centric rather than plot-centric.

However, with Speak, the lack of a structured storyline provides slight repetition in events and chapter style. The uniformity and little change to it all connect directly to Melinda’s mental state, the primary focus of the book. It’s a good stylistic choice and makes the most sense for the way that this story is told, but it might be disappointing for readers who come in with expectations for a book that follows a more generic outline.

By banning a beautifully written story such as Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, schools and parents are shutting out outlets for understanding and relating to teenage characters who struggle with the same mental health issues and traumas that one in six women forcibly experience in their lifetime.

This story and Melinda’s experience can build empathy and connection amongst students to continue to raise a more aware and considerate generation, rather than one that protests being able to read about such important and relevant topics.

To put it simply, this is a beautifully insightful book on the damaged teenage psyche that sends a powerful message about mental health and is enjoyable to read. A misinformed opinion shared by some adults shouldn’t affect every student’s access to quality literature.

Zoe Lodge is a senior and this is her second year at the Eagle Times! When she isn’t writing (for the Eagle Times, for school, or creatively), you can...