Protest Music: Hip-hop, Rap & Revolution

Collage of hop-hop and rap albums from groups and artists mentioned throughout the article. Photo collage courtesy of Sofia Perrine under Fair use

In the early stages of hip-hop and rap, these genres were seen as a “fad” that would pass through the music industry. Despite this, hip-hop and rap continue to be present in mainstream spaces, refusing to back down.

Hip-hop and rap lyrics seek to ignite and inspire, legitimizing how the historical oppression Black Americans have faced in the US continues to impact the Black community. From the progressive hip-hop and rap of the late 80s and 90s groups and artists such as N.W.A. particularly their hit song “F*** Tha Police”, are clear and direct using provoking language to strike back against police brutality.

“F*** the police comin’ straight from the underground

A Young ***** got it bad ’cause I’m brown

And not the other color so police think

They have the authority to kill a minority

F*** that s***, ’cause I ain’t the one

For a punk motherf***** with a badge and a gun

To be beatin’ on, and thrown in jail

We can go toe-to-toe in the middle of a cell”

“F*** Tha Police” is one of the most recognized political songs that has established hip-hop and rap counterculture messages. In this way hip-hop and rap do not fill space but instead transform greater political conversations, motivating protest against systems of oppression.

Hip-hop and rap have faced great backlash stemming from a misconception that the lyricism glorifies violence due to the number of profanities used or drugs referenced. Such criticism contributes to a false notion that hip-hop and rap are less intellectual, inauthentic, and too commercial in their form.

Duke Professor Marc Anthony Neal addresses such misconceptions in a “HISTORY this Week” podcast episode on the “Birth of Hip Hop”, stating, “America is violent and more importantly America has been violent to black people. I think hip-hop in its previous form has tried to be reflective of the world…there’s a way to do that and create great art at the same time.”

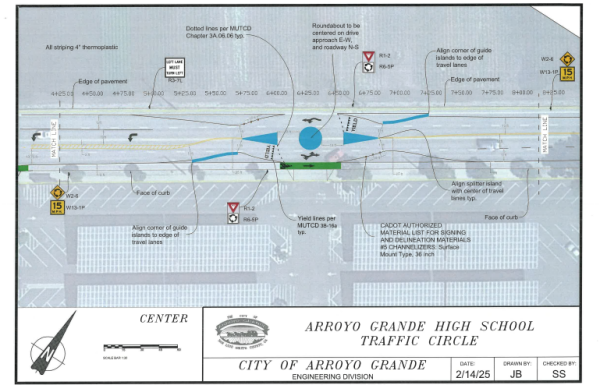

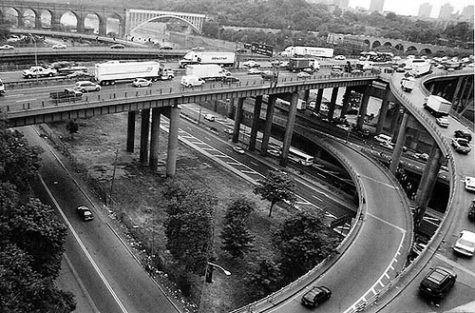

Photo Courtesy of Creative Commons

Neal goes on to expand upon the history of hip-hop as a cultural movement of the 20th-century that sought to redefine music and art. The Bronx is particularly significant to hip-hop as demographics shifted within the 40s and 50s in response to changing immigration laws in New York, more particularly as Black and Latinx migrants and immigrants began to settle within the city.

As these different cultures meshed, these groups shared their music, dance, and culture which helped form the foundations of hip-hop. The later displacement of Black, and Jewish communities due to the Cross Bronx Expressway during the 50s and 60s, as well as a great economic decline, helped shape the birth of hip-hop.

In a research paper “Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form,” Harvard professor Marcyliena Morgan and UCLA professor Dionne Bennett define 5 elements of early Hip-Hop, “(1) deejaying and turntabalism, (2) the delivery and lyricism of rapping and emceeing, (3) break dancing and other forms of hip-hop dance, (4) graffiti art and writing, and (5) a system of knowledge that unites them all… Hip-hop knowledge refers to the aesthetic, social, intellectual, and political identities, beliefs, behaviors, and values produced and embraced by its members, who generally think of hip-hop as an identity, a worldview, and a way of life.”

Professors Morgan and Bennett later determine the significance of hip-hop as a youth-driven cultural movement. Neal identifies the youth impact on hip-hop culture through the tradition of the dozens which was further developed by teens in the Bronx to incorporate oral storytelling and lyrical dexterity in both hip-hop and rap. While commonly conflated, Professors Morgan and Bennett assert that the disparity between hip-hop and rap is a result of hip-hop’s development as a cultural movement and while rap stems from hip-hop it primarily focuses on the hip-hop element of lyricism. Youth impact on early hip-hop culture is a significant component of the foundations of hip-hop and rap and its greater political developments today.

Hip-hop and rap have grown and spread beyond the borough of the Bronx into more mainstream spaces successfully defining a new era of music and art. The socio-political and economic influences of the Bronx and the greater development of hip-hop culture as a voice for young Black Americans in America have made hip-hop and rap intrinsically political. In this way, hip-hop and rap in the US have developed into a subversive medium used to express and identify the Black struggle in the US against many socio-political and systemic issues that continue to affect Black Americans.

Yoh Phillips, a journalist from the hip-hop magazine Okayplayer, further expresses the political aspects of hip-hop and rap in an article about political rap that had defined former President Donald Trump’s 2017-2021 term writing, “Hip-hop was first called the ‘CNN of the Ghetto’ by Public Enemy’s Chuck D, a perfect analogy of how the culture is meant to communicate with the disenfranchised and marginalized communities unrepresented. The rapper is the reporter, a vessel capable of speaking to and for the hood and its inhabitants.”

The aforementioned hip-hop group Public Enemy’s political influence is undeniable. From their 1988 album It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back, Public Enemy redefined political hip-hop culture and music. The conceptual album features revolutionary songs such as “Caught, Can We Get A Witness,” which seeks to use hip-hop and rap to give a voice to Black Americans.

Photo Courtesy of Creative Commons

Public Enemy’s hip-hop legacy and historical Black revolutionaries such as Malcolm X later inspired other political hip-hop groups such as Dead Prez, particularly their 2000 album Let’s Get Free. The album conveys anti-capitalist and socialist beliefs through purposeful lyricism advocating for greater social change outside of the current institutions that prevent Black Americans from truly “becoming free.” Songs including “Police State,” “Propaganda,” and “They School” address systemic barriers in the US; such as the racist police systems, propaganda perpetuated by former President Ronald Reagan, and other political figures they believed to be against Black Americans and how underfunded public schools contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline, which has greatly contributed to overburdened and racist prison systems.

Dead Prez later went on to collab with The Evil Genius DJ Green Lantern in the 2009 album Pulse of the People which helped establish a narrative of the Black struggle in the US- particularly in their song “$timulus Plan,” which references how historical economic issues have contributed to greater levels of poverty and current systemic barriers many Black Americans face.

Groups and artists such as Public Enemy and Dead Prez have continued to inspire the global spread of hip-hop and rap outside of the United States. Lesser-known artists such as Marcel Cartier and Genocide incorporate hip-hop and rap in their political activism against oppressive government systems. Both artists advocate socialist beliefs against capitalist structures, including apartheid, that have contributed to both social and economic struggles across the world.

Professors Morgan and Bennett further note that “hip-hop has grown in global popularity, its defiant and self-defining voices have been both multiplied and amplified as they challenge conventional concepts of identity and nationhood. Global hip hop has emerged as a culture that encourages and integrates innovative practices of artistic expression, knowledge production, social identification, and political mobilization.”

Such hip-hop expression has been conveyed across the world, but can be especially seen within current conflicts in Iran. Among much political dissent against the governing systems, encroaching and oppressive regulations along with the rampant arrest of protesting citizens, hip-hop and rap have become a new outlet for many to use in their activism.

Hip-hop’s cultural and political influences, both in the United States and globally, are objective. However, the current discourse on political hip-hop and rap in the United States centers on the commercial aspects of such music. Where many return to the belief that hip-hop and rap lack intellectualism and authenticity or have deteriorated as cultural art forms in mainstream spaces in an effort to appeal to greater consumers of the music industry.

Neal states that “a lot of it [such criticism] has to do with what kind of hip-hop catches the attention of corporations trying to sell it, and very often the most popular hip-hop is not reflective of the entire genre.”

Photo Courtesy of Creative Commons

Such hip-hop and rap discourse have contributed to a divided conversation where only some music is recognized for its authenticity, intellectualism, and political commentary. It’s important to recognize current artists such as Childish Gambino and Kendrick Lamar who continue to transform mainstream spaces while continuing the legacy of previous political hip-hop and rap artists.

Childish Gambino in particular created great controversy in his 2018 album This is America. At the height of the Trump presidency, Gambino released the album with the popular song “This is America” which directly references the pervasive issue of gun violence. While the overarching theme against gun violence is more obvious to most listeners Gambino continues to make commentary on other social issues impacting the Black community.

“You just a black man in this world

You just a barcode, ayy

You just a black man in this world

Drivin’ expensive foreigns, ayy

You just a big dawg, yeah

I kenneled him in the backyard

No, probably ain’t life to a dog

For a big dog”

Such lyrics reference the prison system through the use of “barcode” and “kenneled” as well as the hypermasculinization black men face in Gambino’s lyrical choice to refer to being “a black man” in America as a “big dog”. Through sparking controversy within mainstream spaces Gambino contributes to a greater political conversation.

Hip-hop and rap continue to infiltrate the mainstream music industry. As this occurs it does not take away from hip-hop and raps authenticity or political intellectualism that is inherent to the culture. Revolution and protest can occur concurrently within such mainstream spaces, as artists continue to push boundaries and successfully create greater cultural representation while continuing to perpetuate hip-hop and rap’s counter-culture themes and political messages.

Sofia Perrine is a senior and a returning staff member of the AGHS Eagle Times. Despite not considering herself much of a "writer" she finds journalism...