Invisible conditions and their understated impact on students

More people are impacted by chronic illnesses and disabilities than most students likely realize. Having conversations about how people’s needs differ and listening to their stories could lead to a greater understanding of the struggles these students face daily.

Makena Massey smiles for the camera with her service dog, River.

“I feel people definitely interpret me as being normal when I have illnesses and other things underneath,” said Makena Massey (‘22).

This is a day-to-day reality for many AGHS students who live with what has become known as an “invisible disability” –a chronic illness, disability, or other condition that impacts necessary activities such as movement, socialization, cognitive function, and participation in school, yet rarely is apparent to others.

Students with such conditions are often in the same classes, sports, and other activities as their peers, yet they face obstacles such as painful symptoms, excessive absences due to particularly bad episodes or medical visits, feeling isolated, extreme stress from missing assignments, fatigue, and even guilt for not being able to function at the same pace as their peers. School on its own can be tough before these layers are factored into the equation.

It can be especially difficult when classmates are unaware of what students with invisible disabilities are experiencing on a daily basis and say or do things that are harmful without even realizing it.

Some may be surprised at how many students and staff at AGHS are impacted by an invisible disability. While it may be intimidating to talk to these individuals about how these conditions affect them, possibly out of fear of saying or doing something wrong, everyone benefits from these conversations and the awareness that they help to establish.

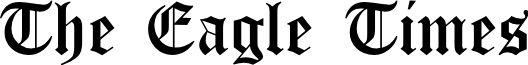

Below are the stories of three students who are currently navigating life with an invisible disability or chronic illness. At the end is a gallery of AGHS staff responses to a survey about their experiences with working with disabled and chronically ill students.

Makena Massey (AGHS ‘22)

I have [been diagnosed with] Ehlers Danlos Syndrome type three (EDS) and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) for over a year and a half now. My symptoms include chronic pain in my joints, headaches, dizziness, low blood pressure, subluxations, and just overall weakness.

My school attendance is affected because I [often] don’t feel well enough to come to school… Sometimes in class symptoms occur and I can’t just leave so I have to deal with that.

Even though I may appear fine, I could be having an awful pain day or my brain fog could be insanely awful… I feel people definitely interpret me as being normal when I have illnesses and other things underneath.

A lot of students find [my condition] depressing. They’re always asking why I have a service dog and I can’t give them the full reason because they find medical stuff scary or intimidating… they get really quiet [and] no longer speak about it.

People are like, ‘Hey, why do you have a dog?’ and I’m like, ‘Your mom’.

People think that I walk around with a dog just for funsies… that he’s just a cute accessory, but in reality, when I need him, I really need him. If my chronic pain is acting up, his tasks are so helpful to me. His tasking for anxiety [also] helps keep the pain under control because anxiety feeds the nerve endings and makes my pain even worse.

River’s handle on his vest allows me to hold [onto him while he does] forward motion recall and follow people or go in the direction of the traffic and it takes the pressure off my joints and allows him to carry [the weight].

If I’m having anxiety, feel like my blood pressure is low, or I’m dizzy, he can go on top of my legs and perform deep pressure therapy [which helps] push blood back up to my head to raise my blood pressure as well as… [reduce] any anxiety I’m feeling.

Because of my POTS, bending over and changing positions [makes me] dizzy and my heart rate can go up easily, so he’s able to pick things up that I drop.

I had some sort of virus that made my EDS flare up, which is why I got diagnosed with it. It was manageable as a kid, then it sort of showed its ugly head and now I have chronic pain… viral infections and any kind of major trauma can trigger things like that.

I am on quite a lot of medication… for GI issues,… nausea, and anxiety because anxiety comes with chronic illness and it feeds it, and chronic illness feeds anxiety, so it’s just an endless cycle. I’m also on pain medication, which I’m currently trying to up my dosage for…[but] it’s giving me a lot of symptoms and that’s hard to deal with in school.

I’m in physical therapy every week… to strengthen muscles and [help prevent] joints from dislocating, I see my therapist for anxiety and depression…, and I see my pain psychologist to try and rewire my thoughts around pain because that affects my personality a lot.

All of my teachers are aware of my condition… Some of them have been really accommodating… and then some others have been not so accommodating and have been very rude when I’m asking what I missed [so] I have to ask other classmates… and I don’t get all the information.

Right now [my mom and I are] looking for a wheelchair. In the beginning, [my mom]… discouraged it, but she saw my pain more and [saw] all my doctors agree that this is a long-term thing rather than short-term…[Parents] want to think they have a healthy kid [and] did everything right, but… it’s not something anyone can control.

[I wish people could] know that [I have] a dynamic disability… it doesn’t affect me every day. I can go from feeling amazing to feeling like dog poop in a snap. Sometimes… when people want me to… do things that require a lot of effort I [have to] say no and they get disappointed. I just want them to be understanding rather than thinking that I don’t want to hang out with them.

And you know, I have the dog for a reason rather than just as an accessory, and I’m not training him for someone else. I get a lot of [this] in grocery stores:

‘Oh, when are you giving him back?’

‘No, he’s actually my service dog.’

‘Oh, you’re training him?’

‘No, he’s fully trained’.

‘Then what’s he for?’

‘ I have a condition.’

‘But what do you have?’

‘It’s POTS.’

‘But what is that? Can you like, give me some detail?’

Like, they want to go in-depth when dude, I just met you in the yogurt section.

Also, I have a name. My name is Makena, not ‘dog girl’.

Sophie Long (AGHS ‘22)

I found out over quarantine that I had ADHD because I started seeing a therapist… I was actually doing an assignment in psychology about ADHD and I was reading about the symptoms, and I was like, that’s kind of familiar to me. So I started looking into it more. And… my therapist was like, yeah, you do have ADHD.

ADHD is a dopamine deficiency disorder… and quarantine took away everything that was giving me dopamine and made me transition from having mild ADHD to moderate to severe ADHD now.

School is probably one of the heaviest places that I’m affected… I have a hard time remembering things I need to do or remembering deadlines.

There are also more severe aspects of having ADHD like executive dysfunction [which] kind of feels like being trapped in your own body for me, like, I have homework in front of me. And in my mind, I’m thinking,… ‘what are you doing, you’re just sitting here, you’re not doing anything, do the homework’. And I literally cannot get my body to do it. Some people also call it ADHD paralysis.

With ADHD being a dopamine deficiency disorder, it means that I follow what is gonna give me dopamine, and I don’t get to choose the one that’s gonna make it.

A lot of people are like, Oh, everyone’s a little ADHD… But what I think a lot of people don’t understand is that when you actually have ADHD all of [the symptoms] are super polarized. It’s a constant struggle rather than once in a while.

[School] is set up for neurotypical people… a lot of the way that it’s set up is really hard for neurodivergent people to succeed in… it’s just not an environment that caters to that same expectation. You have way more hurdles placed in front of you, but you’re expected to do the same thing at the same time [as your classmates].

ADHD is so much more complicated than it’s portrayed generally… I was not ready for all of the other things that this comes with. But the diagnosis is also good because I can look back on my life and be like, “that’s why I did that thing” or “that’s why I do the things I do”. So it’s a bit of a relief to have that make sense.

How people [with ADHD] interact socially with people is a lot of times different than how neurotypical people interact. I can talk a lot, obviously. Another ADHD thing is I get super excited about something and want to share it with a friend… And a lot of times, I’ll start talking about something, and I’ll get shut down immediately. And that just like, kills all motivation to talk to the person. It’s not necessarily their fault, but it’s hard to interact in that way.

Quarantine is literally worldwide trauma… And we’re not doing enough for the mental part of that. There’s financial relief and stuff to help people get through it… It wasn’t even until after the fact that I like realized how bad my mental health was in quarantine. I basically slept through an entire year… I’m glad I’m on the other side of that, but also, I’m coming out on the other side of it with so many more problems than I had before. My brain changed chemically… like my mindset towards everything school-related and the things I used to like prioritize.

[There’s] all this coverage on the very obvious disabilities which is great, but the invisible disabilities get overlooked or misunderstood, because they’re not obvious.

Will Howell (Sonoma State University ‘23)

At the age of three years old, I was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome. This is a mild form of Autism. It started off when I was a toddler and my parents noticed that I started crying a lot more than a usual toddler. After multiple weeks of psychiatric evaluation, the psychologists determined that I have Asperger’s syndrome, which basically means I have social anxiety frequently, I get a hypersensitivity to… most of my senses, and I have stuttering issues. Sometimes I get very narrow, narrow interests, and I have a lot of panic attacks too.

In the American education system, it’s more so about passing than it is about learning. And in this so-called “learning system”, there is the very important job of catering to an autistic individual. It mainly focuses on multiple different kinds of tests, which determine how well you do in the class overall, which is very not friendly to those who are experiencing anxiety over so much going on.

In my personal experience, special education in high school can be a little bit lackluster, especially when it comes to substitutes who don’t know what they’re doing, or, or teachers who are just there to get a paycheck. A lot of accommodations don’t really prepare you for college. For example, one accommodation for special ed, at least in New Tech High [allows you] to turn in late assignments on time… In college you can’t turn in late assignments, that’s on you. So if anything it doesn’t… help disabled people out, it just acts as a crutch, almost like they’re capable of doing less than the average person. That’s the difference between an accommodation and a crutch, and the public education system has a hard time trying to figure out which is which. Unreasonable accommodations can lead to having a lot more autistic people struggle in the university system. There’s a reason why only 46% of autistic people go into higher education.

Outside of school, just going on a walk can [sensory] overload you a lot of times. What may seem like a normal bus passing by you sounds like an air horn. Sometimes when the sun comes out, it’s very irritating to your eyes whereas a normal person wouldn’t really mind it. Simple car honking can make you jump in shock, and a rude person on the road insulting you can cause you to have a meltdown. Life’s full of unexpected surprises for an autistic person.

Sometimes when you’re in a situation with strangers, you don’t know how to react. The scariest part of all is when stuff gets thrown at you and you don’t really know how to react to the situation, and that leads to people thinking that you’re stupid, or that you don’t know anything, and that can really suck.

I personally never have had a hard time with [explaining my diagnosis], most people understand… it actually became a running joke in my workplace during summer for me to use autism as a dumb excuse for everything. It actually helped me integrate myself with other non-autistic people and find connections and sort of bring humor to what can be a hard subject for people like me.

[My peers] don’t really treat me any different. They treat me just like any other kind of person. And of course, there’s the running joke of me using it as an excuse for stupid stuff. And of course, they go along with that, but they understand that I get overwhelmed. And a lot of times when [my roommates are] playing video games or having a party, I’m in my room. Not because I’m antisocial, but because I need to recharge my social battery, as so many autistic people struggle with. And it’s a matter of kind of calming your senses. When you get a sensory overload, it drains your energy, and sitting in my room watching YouTube or TikTok helps me slowly gain my energy back, like an iPhone battery.

I suffer from depression and suicidal thoughts, and I’m currently on antidepressants for it. I’ve been in the ER for this kind of stuff. And the worst part about it is that I feel like I’m such a privileged person. I’m white. I’m male. I come from a higher-class family. I have my college paid for me. And yet I’m feeling sad while there are people out there who have lives are absolute dog water, yet they’re able to find happiness. So sometimes I do get myself up over it. Why am I sad when I have so much going for me?

I know definitely when it comes to autistic people, they have it a lot harder in their minds. Even though it may not look like it, there are 100 million things going on in their mind at the same time. It’s really difficult to process every single one, like imagine trying to work at Burger King 22 hours a day. Eventually, it can really wear you out and you’re going to start slipping up. And the two hours of rest that you get are not going to be enough to be able to process everything.

I recommend a good self-care app called Finch. It’s kind of like a self-care pet app. It gives you self-care tips and has a cute little pet that you get to raise and dress up and it does a really good job of helping you remember that you matter and take care of yourself, it’s free on the App Store.

I live with three frat boys. I’m not in a fraternity myself, I’m the opposite of frat-boy culture. I enjoy playing Dungeons and Dragons, playing Zelda, I use discord and I don’t really use Snapchat, I’m the opposite of a popular kid. So when I’m hanging out with my roommates, I kind of don’t feel like I fit in, I think a lot of times because of autistic culture. I have a hard time trying to find conversation topics especially when they frequently talk about their fraternity that I know nothing about because I can’t put myself into fraternity culture.

Sometimes you have thoughts:

‘Are they looking at me weird?’

‘Did I forget to do something?’

And then those thoughts linger with you, they don’t go away. You sometimes wonder if everybody’s judging you. You begin to have a battle with your own thoughts, and that can lead to some pretty scary situations… And even though you may look fine to others, it’s kind of a battle in your mind eternally.

Erika Schiesl is a senior and is excited to be a part of the Eagle Times again this year. Aside from writing stories, she also enjoys photography, art,...